INTERNATIONAL newsrooms that report on Africa are often full of white journalists, such as me. But just how white or how ethnically diverse are they? To get a better idea, we sent a survey to 47 international media outlets that cover Africa and spoke to some of the Black reporters they employ.

This conversation isn’t new. Foreign journalists have frequently been accused of racism or mischaracterising the countries they report on – whether justifiably or to deflect attention. We wanted to provide a quick snapshot of diversity in our industry today, to spark debate rather than provide any definitive answers.

We focused on journalists of colour reporting on Africa for practical reasons. We recognise that these questions are pertinent worldwide, but the continent is both my and African Arguments’ focus. We’re aware of the risk, however, that this approach might reinforce “typecasting”, as Howard French puts it: the expectation that Black reporters take on “Black” beats such as Africa, while they are excluded from reporting on, say, Asia.

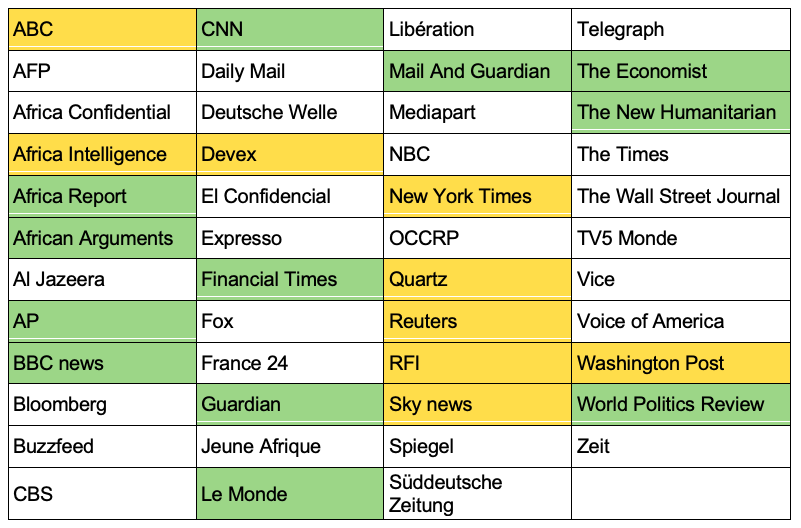

We sent the survey to 47 newsrooms. Of the 21 that responded, 12 provided answers to some questions (green); 9 declined to respond or directed us to previous reports (orange). The rest did not respond at all despite multiple reminders (white). The full answers are available here.

In addition to the questionnaire, we spoke to several Black journalists about their experiences. They all asked to remain anonymous, a sign that this topic remains highly sensitive. This is what we found.

Everyone publicly agrees diversity is important

The survey’s first question asked about the importance of diversity. Unsurprisingly, the newsrooms that responded stressed that they consider this very important and that they strive to recruit more diverse teams.

For example, the Associated Press wrote: “Diversity and inclusion are of the utmost importance”. The Economist stated: “We will produce better journalism if we draw from a broader pool of people, both because we are more likely to find more talent if we look for it more widely and because a diverse staff will bring a breadth of experiences that, in itself, will improve our debates and hence our journalism”. Le Monde said: “the lack of diversity – social, cultural, and of origins – cuts us off from certain categories of the population [and] can also make us miss trends, hidden signals and underlying currents.”

The reporters we spoke to agreed that their origins allowed them to do better journalism. “I think it’s an issue that there aren’t enough journalists of African origins,” said Aïssata*, who was born in France of African parents (we’re keeping her background vague to maintain anonymity).

She stressed that her white colleagues did good reporting too and that Black journalists born in Europe might also have an “Eurocentric” perspective. Nevertheless, “we’re less in an unconscious ‘white gaze’ on Africa when we have African origins,” she said. “The difference is to have been subjected to racism, which influences one’s perspective on Africans and their cultures.”

Natasha, a journalist who was born in an African country and grew up in France, concurred but added that her background had also been used against her. “In Anglophone newsrooms…there’s no suspicion that you lack objectivity…[but] in France, I was told ‘you’re from [African country X] so you can’t work on [that country]’”, she said. “You have value when you open your contact book, but you don’t have value to tell the story yourself because they’ll say that you’re not objective.”

Counting identities is not simple

The second part of the survey looked at the proportion of journalists of colour among the outlets’ contributors. 11 newsrooms provided statistics regarding their staff. Their teams ranged from being 12% non-white to 100%. The median was 20%.

Only five outlets provided data regarding the freelancers with whom they worked. Those generally had a greater proportion of journalists of colour working freelance than on their staff.

Not all the newsrooms we contacted were legally allowed to answer this set of questions. In France, the ability to collect statistics on ethnicity is restricted. As the spokesperson for Le Monde wrote: “Sorry for such a vague answer, French laws impose this on us!” The French government believes that limiting the collection of such data will help guarantee equality. But this approach’s effectiveness is often challenged.

“If you don’t have that data then you can’t address [the issue],” said Josie Dobrin, head of Creative Access, a UK social enterprise that supports people from under-represented backgrounds to get into creative jobs. She explained data also can help work out where the problem lies – such as whether it’s most pronounced in recruitment, hiring, or retention.

Detailed statistics can illuminate whether there are discrepancies across different kinds of roles. The Guardian’s 2019 UK Ethnicity Pay Gap report revealed that people who identify as BAME (Black, Asian and Minority-Ethnic) are less represented in leadership roles and editorial positions (12% compared to 22% in non-editorial ones). Similarly, TV outlets that published such data found that the proportion of journalists of colour “on-screen” was significantly higher than off-screen (27% compared to 10% at the BBC, for example).

While ethnic data can reveal discrimination, it has its limits. In particular, broad groupings such as “BAME” or “people of colour” ignore distinctions within this category. These discrepancies can be significant, as The Economist’s answers to us revealed. They were the only large outlet to provide us with a breakdown in the ethnicities of their staff, which were: Asian 10.4%; Black 1.5%; Mixed 3.8 %; Other 7.7%; White British 50.7%; White Other 25.9%. The statistics at the New York Times are similar, according to their 2019 diversity report.

Both outlets notably have a lower proportion of Black staff and higher proportion of Asian staff than the populations of the countries in which they are based, respectively the UK and the US. Such data raises questions – beyond the scope of this article – on whether there’s an “ideal” composition of a newsroom and of whom the media should be “representative”.

Discrimination takes many forms

How does discrimination happen? In a recent interview, Laurent Joffrin, former editor of Libération, described the process from the hiring side. “Often, [our] recruitment is done by co-optation so people tend to introduce people…who resemble them,” he said. “I don’t think there’s necessarily a mechanism of racial prejudice. However, there’s unavoidably a mechanism of social reproduction.” The French newspaper – which didn’t respond to our survey – employs 150 staff, of whom just three are Black.

Dobrin cited many other barriers for people of colour getting into media, such as parental pressure against creative jobs, unpaid internships, recruitments advertised by word of mouth, and discrimination against non-Western-sounding names. “There’s so many obstacles that people are facing. And that’s just getting in.”

But the barriers don’t end once journalists of colour are recruited. The Black reporters we spoke to emphasised that discrimination continues in the job.

“The diversity issue for me goes beyond the racial makeup of the newsrooms,” said Gaelle, an African journalist reporting from her home country. “Our editorial freedom is limited because we still have to tell the stories we pitch through a white lens…I [also] discovered that…the stipend I receive for [articles] is lower than what the reporters coming to Africa would get.”

Mercy, a young journalist who grew up in the UK and whose parents were born in an African country, described struggling to fit in at a prestigious outlet where she was the only black person and one of few journalists from a modest background. At home, she would research conversation topics to relate to her white upper-class colleagues as they talked about their ski trips and gap years. Despite her efforts, she said, she didn’t get the same opportunities as her peers. She saw this as her own failure, which hurt her self-confidence for months.

Natasha faced up to discrimination much later in her decade-long career. She said that when she wasn’t offered the same opportunities as her white colleagues, “I was telling myself ‘hang on, it’s not an easy job’”. It was only when her husband, a white journalist, expressed outrage at her recounting her experiences that she accepted that it was because of her skin colour. “I already knew that it wasn’t right, but to have someone from the outside [say this], it was a shock,” she said. This led her to take a new career path. “For a long time, I was certain that working a lot, working hard, would open all doors. And today, I know it’s not true.”

When it comes to tackling discrimination, there is a wide range of approaches. Some outlets only make informal efforts, while others have set themselves specific targets and backed them up with big budgets. Dobrin emphasises that there is no silver bullet. “The organisations that are the most successful are the ones that embed diversity in everything they do,” she said.

For many journalists like Aminata, a French freelancer with African origins, the time for addressing these issues is long overdue. “I think we all hope that it won’t be just words and that newsrooms will really question themselves, and really ensure that they hire Black journalists, amongst others, who have talent – because there are many,” she said.

“I’m waiting to see what this discussion will bring. It’s not the first time we’re having it.”

(ARTICLE ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED BY AFRICA ARGUMENTS)