THE small fiberglass boat had begun to take on water not long after the engine stopped working. Its six passengers started bailing it out, not knowing how long they could keep the sea at bay.

Waleed, a Tunisian man who, along with five others, was hoping to cross the Mediterranean for a better life in Europe, estimates they removed water from the boat for roughly five hours.

“We were so desperate,” he said.

Then, at first daylight on Sept. 20, the crew of a rescue vessel spotted them through binoculars. They saw Waleed and the others waving and directing a laser light at them.

The migrants were a few miles away from the Geo Barents, a rescue vessel operated by the charity Doctors Without Borders. It had been patrolling the Central Mediterranean off conflict-wracked Libya since earlier that month. A team from the charity, known by its French acronym MSF, was immediately dispatched.

They found six men: three Libyans, two Tunisians and a Moroccan. The group had embarked a day earlier from Libya’s coastal town of Zawiya, a major launching point for migrants attempting the dangerous voyage. All six say they were fleeing difficult or threatening situations in Libya, where three of them had relocated years before due to economic troubles at home.

North African Arabs represent a large and seemingly growing proportion of the migrants who are trying to reach Europe via the Mediterranean.

According to recent numbers published by Italy’s Interior Ministry, three of the top 10 countries of origin for migrants arriving in the country in 2021 were North African. Tunisians alone accounted for 29% of the migrants, followed by Egyptians with 9% and Moroccans with 3%.

Late on Monday, the newest influx to Italy came by sea when around 700 migrants crammed into a rusty fishing boat reached the Italian island of Lampedusa, located mid-way between Tunisia and the Italian mainland. Many appeared to be men from North Africa or the Middle East.

Their increasing numbers also point to precarious situations in their home countries, where government resources are strained by burgeoning youth populations. Many have already spent harrowing years inside Libya, once a destination for migrant labor because of its relative wealth.

Libya’s descent into war and lawlessness over the past decade has made it a hub for African and Middle Eastern migrants fleeing war and poverty in their countries and hoping to reach Europe. The oil-rich country plunged into chaos following a NATO-backed uprising that toppled and killed longtime autocrat Moammar Gadhafi in 2011.

This month’s sea crossing was Waleed’s eighth attempt to reach Europe since 2013, he said. For the past 17 years, the 42-year-old father of two from the city of Tunis had worked as a chef in neighboring Libya. He described life there recently as nightmarish.

“Any Libyan can beat you, insult you, take your savings, and you (as a foreigner) can’t do anything,” he said.

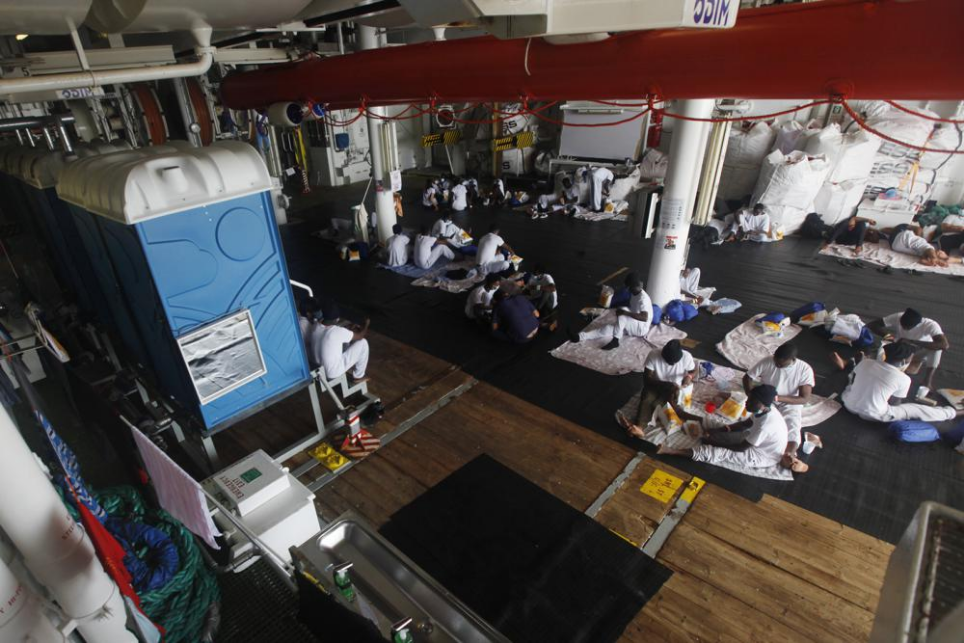

Waleed spoke to The Associated Press aboard the Geo Barents as he and other migrants waited for disembarkation at a port in the Italian town of Augusta, where they will first face quarantine for coronavirus and then processing, at which point they claim asylum.

Waleed’s ship mates included another Tunisian, Kamal Mezali, who had worked as a sailor in Libya, and Mohamed, a 30-year-old Moroccan barber. Waleed and the barber asked to be identified only by their first names, to avoid endangering friends still in Zawiya.

Hailing from Morocco’s ancient city of Fez, Mohamed arrived in Libya in March 2019 and settled in the western town of Sabratha. Last year, militias stormed his house and seized his passport and savings. That’s when he decided to leave.

His first attempt to cross the Mediterranean was in May 2020, but he was intercepted by the Libyan coast guard, which he said released him for a bribe upon returning to port. He was reluctant to try again, fearing he could drown.

His resolve came back when an enraged Libyan customer pulled a gun on him for allegedly failing to answer calls to set up a hair appointment. He was going to kill me,” the migrant said. “Libya isn’t a place to live.”

Mohamed got a spot on a small boat, just 4 meters (13 feet) in length. The six men had a 40-horsepower motor and a smaller 25-horsepower one as a spare.

First their main motor gave out, then the spare while they were still not far from Libya’s coast. One of the Libyan passengers called a contact, who brought a replacement. But none of the motors were designed for such a lengthy trip, and a few hours later the third motor went quiet.

By the time the rescue crew reached them, they were nearly 40 nautical miles off the Libyan coast and the boat was low in the water. They had only one frayed life jacked on board.

According to the United Nations, over 1,100 migrants were reported dead or presumed dead off Libya this year, but that number is believed to be higher. Around 25,300 others have been intercepted and returned to Libya’s shore since January. That’s more than double the number from 2020, when about 11,890 migrants were brought back. The spike comes after overall arrivals, but not deaths, declined during the height of the pandemic in 2020.

Italy says that 44,778 migrants have arrived on its shores so far this year, double the amount from the first nine months of last year, and roughly five times the number from 2019. The increases come after a route through the Eastern Mediterranean via Turkey was blocked, and while the movement restrictions and economic fallout of the pandemic are at play.

Mid- to late summer is typically a peak time for attempts on the Central Mediterranean route because of good weather. Rescues along this route have become routine during the warmer months.

In recent years, the European Union has partnered with Libya’s coast guard to stem sea crossings. Rights groups say those policies leave migrants at the mercy of the sea, armed groups or confined in detention centers run by militias that are rife with abuses.

The other three passengers on the boat with Waleed, all Libyans in their 20s, said they risked their lives in the Mediterranean because of the deadly power wielded by militias in the country. Though not statistically a large number of migrants, Libyans have their share of horror stories.

When east-based military commander Khalifa Hifter launched his offensive on Tripoli in April 2019, militias in western Libya mobilized and recruited fighters to counter the attack. Mohammed, a 29-year-old engineer, spoke out against joining the fighting. He asked only to be identified by his first name for the safety of his family back in Libya.

Then he received death threats from militias. In March 2021, he said armed men opened fire at him while he was driving near Tripoli. He narrowly escaped with his life.

Earlier this month, a friend offered him a seat on the boat. He left behind a 19-month-old baby and a pregnant wife, deciding he’d rather die at sea than be killed at home.

And that’s what he thought was going to happen when the group grew exhausted hauling water from the boat.

“We all were tired and powerless,” he said. “We thought that this is the end.”

- AP