Farsan Madjdi and Badri Zolfaghari

SOCIAL entrepreneurs embrace social as well as economic value. They create ventures that aim to meet social needs. They are not only risk-takers and proactive innovators but have a strong ethical fibre. They are compassionate and morally motivated to create social ventures.

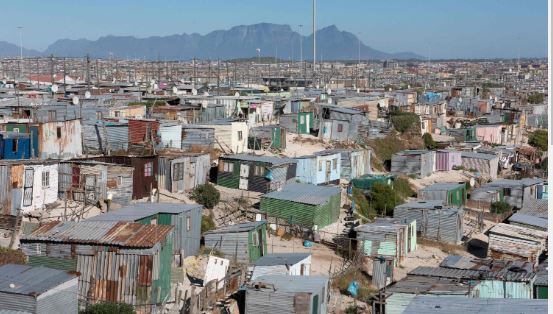

One such social venture is Regenize, founded by Chad Robertson and Nkazimlo Miti in the Cape Flats in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

The two social entrepreneurs wanted to make recycling a rewarding endeavour and educate young people about sustaining their environment. Their many awards and the global recognition they’ve received are testament to the importance of their mission and value creation, not just for their communities but beyond.

Yet, social entrepreneurs such as Chad and Nkazimlo and the ventures they create are not a monolithic group. They can vary in their goals, their motivations, how they judge their situations, and how they build their business in their local context.

Their operating context is shaped by government regulations, policies, financial support (or lack of it), an entrepreneurial ecosystem, and other factors. So, if societies want to promote social entrepreneurship, they must better understand all these motivations and approaches.

Their variety has implications for how advisers, policy makers, incubators or accelerators, and institutes of higher education can better support social entrepreneurs.

Our study explored what motivated different social entrepreneurs to develop businesses that assisted their communities.

We found that social entrepreneurs differed from for-profit entrepreneurs in their venture idea judgements, and strongly relied on their specific social goals and motivations in the creation of social ventures.

Personal goals, missions and social motivations matter

Our study was conducted over a 15-month period with 34 (social) entrepreneurs based in Cape Town.

The entrepreneurs had different professional experiences and were focused on a variety of social challenges. We provided them with three different business scenarios. We asked them to imagine being a founder of one of the three and talk us through how they would build this venture.

The aim was to understand the differences in their judgement, motivation and goals.

We found that the social founders used the same criteria for building a social business. But they differed on the importance they gave to each one. The criteria included market demand, competition, personal knowledge and skills, funding and investment requirements, moral and ethical values and social impact.

The differences depended on the needs of the communities or the specific target groups they were imagining building the venture for. They did this by initially looking inward, thinking and talking about their personal emotions and motivations.

When thinking about the business, they paid particular attention to personal and implicit information attributes. And they said they would have to adapt the selected business scenario to fit with an embedded need.

Embeddedness in this context means that they had an intimate knowledge of and concern for the needs of the specific social group or community. They did not try to keep an emotional distance. Instead they let their emotions play an active part in their evaluation process. This showed inner conflicts or tensions during their decision process.

Other social entrepreneurs focused on the feasibility of the business. For these entrepreneurs, their external governing context was more important because their target audience was broader. But they did also look inward to see if they would find an alignment between the business scenarios and their desired goal of social impact generation.

What we saw was that these two types of social entrepreneurs – the community-driven and mission-driven – focused on different criteria in the beginning of the venture creation process. They were driven by different goals and social motivations when continuing to develop the venture idea further.

These variations have implications for their stakeholders. Community-driven founders are more intrinsically motivated than mission-driven founders who focus on intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Which is why they differ on what they consider to be a social need they aim to address.

These variations suggest that advisers and policy makers should not assume that all entrepreneurs are mainly motivated by profits and wealth generation. They should consider their different motivations. Existing support programmes such as entrepreneurial training focus mostly on assisting entrepreneurs to develop their ideas and related business plans. They focus on generating financial value but not enough on what motivates the entrepreneurs to create social value.

What support is needed

Governmental institutions should pay more attention to aligning their policies and support infrastructure with the motivations of social entrepreneurship.

One way could be through the government adopting a regional approach. The development of local clusters governed by a permanent committee could support the individual entrepreneur by increasing their visibility, connectivity and interaction with other like-minded entrepreneurs or potential stakeholders.

Another way could be through incubators and accelerators that recognise the dual focus of social enterprises: economic and social dimensions.

Building support networks for social businesses could also help, as could facilitating access to funding.

University-linked centres, such as the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship, for example, also pay an important role in bringing together social entrepreneurs and their stakeholders.

Regenize started with the needs of its local communities in mind. But it went on to have broader impact. Enterprises can do this either directly by scaling, or indirectly by helping other ventures to create a similar business model and offering.

But they won’t be successful if they don’t have supportive policies, infrastructure and stakeholders that cater to and understand their goals and motivations for creating their

Madjdi is a Researcher in Entrepreneurship & Innovation, University of Cape Town and Zolfaghari is Senior Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour, University of Cape Town.

The Story was first published in The Conversation.