Ellie Violet Bramley

For the first time in its history, Wimbledon has relaxed its dress code rules. Why are they so strict? Ellie Violet Bramley takes a look.

For the first time in 146 years, Wimbledon has changed its women’s dress code. But, this being Wimbledon, the change is glacial rather than radical: players are now allowed to wear dark-coloured undershorts.

The move has reportedly been made to alleviate the worries of competitors who are on their period. In a statement, All England Club CEO Sally Bolton said she hopes that the new rule “will help players focus purely on their performance by relieving a potential source of anxiety.” It has been welcomed by many of the players. As US pro Coco Gauff told Sky News last week: “I think it’s going to relieve a lot of stress for me, and other girls in the locker room, for sure.”

For tennis historian Chris Bowers, who has written biographies of Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic, the tweak is a case of Wimbledon bowing to social pressure. “Wimbledon was on very uneasy ground,” he tells BBC Culture,”in many ways I don’t think they had much of a choice on this one.” The idea that female athletes should be required to dress in any way other than that which best suits their demands on the court feels quaint and outdated at best, archaic and sexist at worst.

But while some ground has been conceded, the rest of the code remains as straight as the baseline on Centre Court, with competitors being told they “must be dressed in suitable tennis attire that is almost entirely white”; it adds: “white does not include off white or cream”. Trims in different colours are allowed, on necklines, cuffs, caps, headbands, bandanas, wristbands, socks, shorts, skirts and undergarments. But, before players start embracing the rainbow, the code is clear that trims should be no wider than a centimetre. And if there was any concern that players would start pattern clashing, the code decrees: “Colour contained within patterns will be measured as if it is a solid mass of colour and should be within the one centimetre (10mm) guide”. Plus: “Logos formed by variations of material or patterns are not acceptable.”

The all-white dress code has, Robert Lake, author of A Social History of Tennis in Britain, tells BBC Culture, ever been thus: “White hides sweat the best, looks clean, sharp and tidy, representing goodness (aesthetically) and, given cricket connections, also reflects upper-middle-class leisure historically.” Although, he notes, it has evolved in some ways: in the late-Victorian period women were expected to dress in line with “cultural expectations of appropriate dress, so (crudely speaking)… modesty”. In the interwar period, he says, it was more about fashion, in the 1950s it became more about “utility, function, comfort”, and, in “the open era… conventional standards of female attractiveness, perhaps even sexiness” are what became key drivers of what players wore.

Serena Williams wore a Wakanda-inspired catsuit to win the French Open in 2018 – she was banned from wearing it at future tournaments (Credit: Getty Images)

It is not only Wimbledon that enforces a dress code. One recent example of a high-profile player falling foul of the rules saw Serena Williams wear a Wakanda-inspired catsuit to win the French Open in 2018 – her first grand slam match since giving birth. She was banned from wearing it at future tournaments. As one commentator wrote at the time: “What this is really about is the policing of women’s bodies and, in particular, the way in which black women’s bodies are othered, sexualised and dehumanised.”

But even if other tournaments enforce dress codes, Wimbledon is an outlier in terms of the rigidity of its rules. As Keren Ben-Horin, fashion historian and co-author of She’s Got Legs: A History of Hemlines and Fashion, tells BBC Culture: “the tennis court has always been an arena in which women have challenged and expanded the boundaries that society put around them. Because Wimbledon has always been a more traditional and conservative tournament than its American or French counterparts it became a stage in which the smallest expression of individualism is greatly emphasised.”

Rules and rulebreakers

What is not appreciated, however, according to Bowers, is that “both men’s and women’s restrictions at Wimbledon have got so much stricter since the 80s.” The code was, he says, “changed from predominantly white to almost all white… they became a lot stricter in the 90s and have carried it on for the last few decades.” Were the kind of styles worn by Steffi Graff and Boris Becker to appear on Centre Court today, he says, they would never be allowed.

So why might there have been a step backwards? Bowers believes it is “all part of Wimbledon being terribly conscious of its brand… There is no reason for Wimbledon to insist that you have to wear a jacket and tie in the Royal Box, but they do,” he says, pointing also to the meticulous stripes of the grass. The strict white dress code is, “all part of the Wimbledon brand that we buy into and associate as much with strawberries and cream as we do with tennis.”

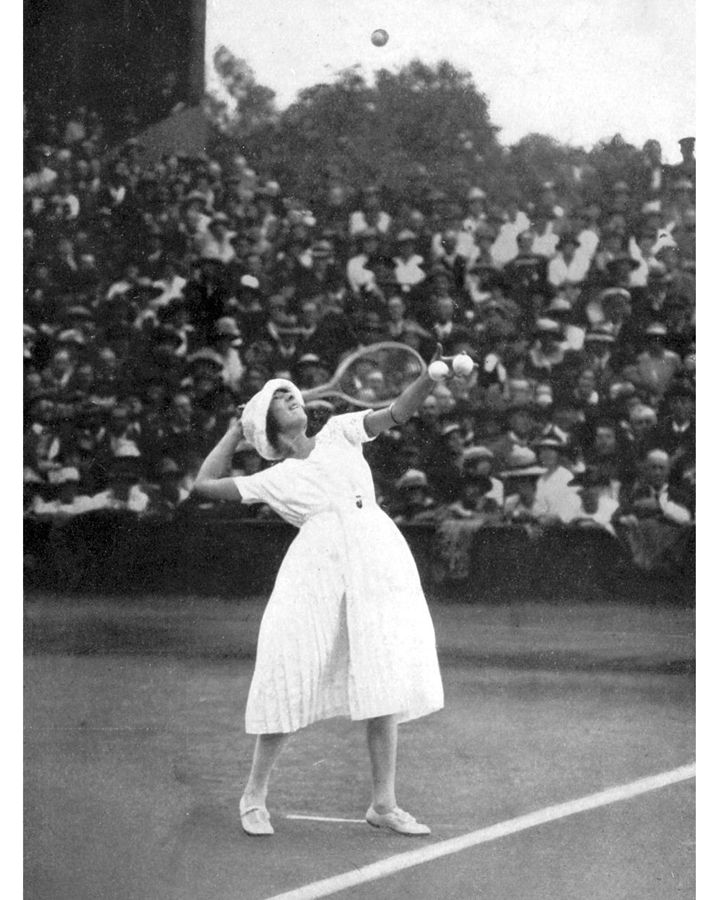

The regime has not been without its challengers. Bowers points to May Sutton who, in 1905, “showed a bit of flesh and they were sort of reaching for the smelling salts”. In 1919, French player Suzanne Lenglen scandalised the press with her “indecent” outfit: corset-less and without a petticoat, she wore a low-neck dress with short sleeves and a skirt to calf-length and silk stockings to just above her knees – she went on to win Wimbledon. When Eileen Bennett turned up on Centre Court in 1934 in a pair of shorts – the first female player to do so – it reportedly sent shock waves through SW19.

In 1919, French player Suzanne Lenglen scandalised the press with her “indecent” outfit: corset-less and without a petticoat (Credit: Getty Images)

In 1949 Gertrude “Gussie” Moran wore a dress by designer Ted Tinling, who had worked at the tournament from the late 1920. “In the US, where she played, Moran used to play with shorts, and she loved bright colours,” notes Ben-Horin, who recently curated an installation about Tinling. “Knowing that the tournament didn’t allow for colour, Tinling added a lace trim to her undergarment which caused a media scandal for the organisers and became a pretence for his dismissal.” Although, she says, “in his memoir Tinling alludes that prior to the scandal his own flamboyant style ruffled the feathers of the organisers.”

In 1985, American player Anne White raised hackles with her all-white catsuit, which she was told not to wear again. Cut to 2017 and Venus Williams was asked to change mid-match, during a break for rain, because of her fuchsia bra straps.

As someone who once fell foul of the strict Wimbledon code, what does White make of the new development to allow for non-white undershorts? For her it comes back to the way the players’ dress relates to the Wimbledon brand: “All of the rules at Wimbledon are what makes it such a special and challenging venue to play professional tennis. I am shocked that the All England Club has decided to allow some colour to women’s attire. I wonder what will be next?”

BBC Culture