Paul Dietschy

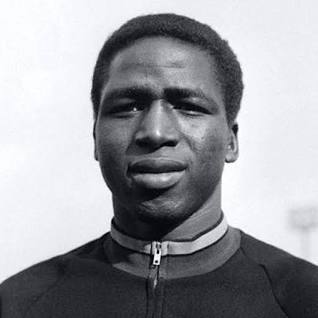

Former Malian footballer Salif “Domingo” Këita, who passed away on 2 September in Bamako, embodied a crucial moment in the history of African football, helping shape its relationship with the world. His influence was also felt in Europe, when he helped shine a light on the rights of French footballers at a critical time.

Born on 6 December 1946, the year that the French West African Cup was created, Keïta (not to be confused with Salif Keita the musician) was also an important leader in Malian football.

As a scholar of contemporary history, with research interests in the political, cultural and global history of football, I have followed Keïta’s career and believe that it’s as important to remember the man and the role he played as it is to remember the player.

Starting out

Salif Keïta grew up in Bamako, Mali, in a family of eight children. It wasn’t easy for him to make his father, a haulage contractor by trade, understand that he preferred football to his studies, even though he eventually qualified to work as a grinder. Football began as an informal activity, even before he started playing in his neighbourhood team in Bamako.

At just 14 he joined the Pionniers club, a product of a form of “progressive” scouting modelled on the socialist countries dear to President Modibo Keïta. His dribbling, shooting and heading skills soon propelled him into the Real Bamako squad. He played in and lost two African Champions League finals, one with Real and the other with Stade Malien, to whom he was loaned for the occasion. He also began to take his first steps in Mali’s national team.

Going to France

But Keïta was aiming higher than national fame. Through postcolonial networks, he came into contact with the directors of French club AS Saint-Etienne, who had good relations with Charles Dagher, a Lebanese trader from Bamako. In September 1967, Keïta was smuggled to Liberia, then flew from there to Orly in France. The directors of the “Greens” (AS Saint-Etienne’s nickname) were not at the airport to meet him and so a young Keïta hailed a taxi to take him straight to the Geoffroy-Guichard stadium.

Keïta was not the first African player to be recruited by a French club. However, the door that was initially opened to footballers from sub-Saharan Africa in the 1950s had partly closed again. On one hand, African federations wanted to keep their players. On the other hand, the number of foreigners playing for French teams was limited to just two. The Malian football federation would accept his sneaking out of the country and the following November sent him a transfer certificate, the key to his playing rights. But even so, at the time French clubs preferred to sign South American or Yugoslavian players.

They offered African footballers harsh contracts and Keïta initially played as an amateur and not a professional, justified by the club’s managers by the fact that he was studying law in France. He was nevertheless paid, eventually signing a four-year professional contract in 1969.

Triumphs on the field

Even though the winter in Forez, in the Massif Central region of France, was harsh, Keïta quickly made a name for himself. At first, he could count on the advice of coach Albert Batteux and the assistance of Rachid Mekhloufi, an Algerian player for the Greens. Playing as a centre forward, Keïta scored 120 goals in 149 matches. In October 1969, he scored the winner against Bayern Munich in the Champions Cup Round of 16.

With AS Saint-Etienne, he won three French league titles and a French Cup. In 1970, his performances earned him the first African Ballon d’Or award. Eager for a change of scenery, he sought to terminate his contract. This led to a bitter legal dispute with Roger Rocher, the president of AS Saint-Etienne.

Suspended for six months, but supported by many fans, Keïta signed with a new club, Olympique de Marseille, in November 1972. Once again he found himself up against the demands of club directors, who wanted to have him naturalised so that they could field him alongside two foreign but European stars, Josip Skoblar and Roger Magnusson. But Keïta refused what he saw as an attack on his dignity as an African man. He became the subject of a local press cabal’s criticisms, with strong racist undertones.

Taking on the world

Keïta then moved to Valencia from 1973 to 1975, where Alfredo Di Stefano had brought him. Spain was not yet the paragon of the beautiful game, but Keïta’s strikes kept finding the net again – until he was injured in March 1975. At that point, Valencia wanted to transfer him in order to recruit someone else. True to form, he defended his sporting and financial interests and only agreed to leave on condition that he was paid the year’s wages due to him and that the club paid its taxes.

Keïta went on to win the Portuguese league as the country began making a name for itself in world football thanks to its stars of African origin – like Keïta, Eusebio and Mario Coluna. At the age of 31, with the club Sporting Lisbon, he finally found an environment in which he could flourish. He won a Portuguese Cup, before playing a final season in the US from 1979 to 1980.

Back home

Keïta retired just as African football was beginning to reveal itself to the world. His life inspired director Cheik Doukouré’s 1994 film The Golden Ball, in which he played the role of a coach.

Back home in Mali, he worked as minister delegate to the minister in charge of private initiatives. After the fall of Moussa Traoré, Keïta opened a football training centre in Bamako. He was then elected president of the Mali Football Federation, serving from 2005 until 2009.

But France has not forgotten him. The directors of Saint-Etienne elevated him to the rank of ambassador for the club and two stadiums bear his name – in Saint-Etienne and Cergy-Pontoise. This was their way of honouring a great striker and a man determined to assert his rights in an environment still marked by a certain condescension towards Africa.

Dietschy is Professeur d’histoire contemporaine, Directeur du Centre Lucien Febvre (EA 2273), Université de Franche-Comté – UBFC.

The story was first published in The Conversation.