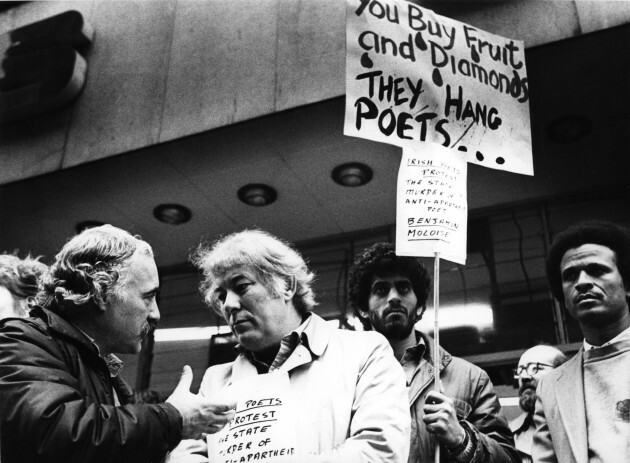

This month marks the 35th anniversary of the Dunnes Stores anti-Apartheid strike in Ireland.

Riyaz Patel

The struggle against the racist apartheid regime in South Africa reached the Dunnes Stores Henry Street shop floor in Ireland in 1984.

Mary Manning, then 21, stepped unknowingly into history on that November morning when she refused to register the sale of the two Outspan grapefruits.

Management had issued a final warning to staff over refusing to handle South African goods. Manning defied that warning. She was brought up to the manager’s office and promptly suspended.

She was complying with a directive from her union – IDATU – not to handle any South African goods in protest against the racist apartheid (apartness) system in the country.

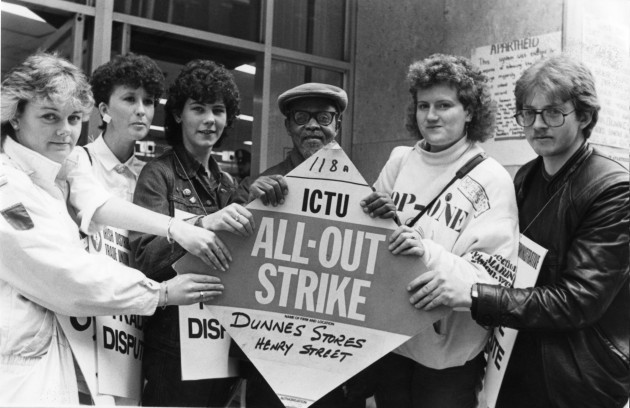

Manning left the store, followed out in solidarity by nine of her colleagues – eight women, one man. None of them would return to work for nearly two years.

Their story is a serendipitous coming together of a small number of extraordinary retail assistants at Dunnes Stores in Dublin who went on strike in solidarity with millions of black South Africans they had never met.

And how those working class heroes helped millions of oppressed black people overcome the vicious and murderous apartheid regime.

At the time, the National Party regime in South Africa had, as official policy, a system of inhumane laws that enforced discrimination against black people in every aspect of their lives. Separate communities. Separate amenities. Separate lives.

The abhorrent apartheid machine brutally enforced these laws drawing international condemnation and a series of boycotts and embargoes were imposed on the country.

Speaking from a picket outside the Henry Street store in 1985, she said that the strike had changed them all and made them more aware of not only the horrors in South Africa, but of other injustices across the world.

“Our battle is nothing to what their battle is.”

“In the beginning, the first few days we thought we would just be out for a few days and that would be it,” Manning said.

“But then we started to learn what was going on in South Africa and it became something much more than a union policy. It became something that we all totally believed in and there was no way any of us could go back and handle South African goods.” Mary Manning

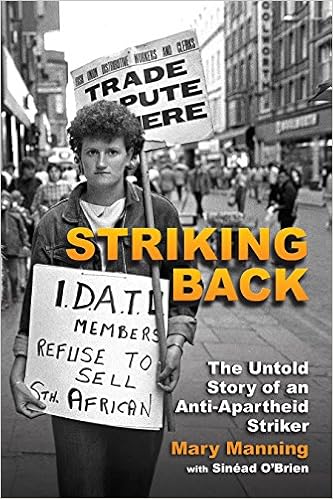

She has since published a book on her experiences of the Dunnes Stores anti-Apartheid strike, the effects on her family life and her life thereafter.

‘Striking Back: The Untold Story of an Anti-Apartheid Striker tells the inside story of a very public political campaign, mixed with a deeply personal story.

One of triumph and tragedy. Of sacrifice and success. But mostly about the selflessness of a small group of Irish working class activists taking on the

entire Irish Establishment… and winning.

The head of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement Kader Asmal publicly praised the strikers soon after their action began.

Initially, though, Manning and her fellow strikers found little support from other circles. Other unions did not strike in support with them, and they received abuse from the public and their Dunnes Store co-workers.

Soon after their strike began, they were joined on the picket line by exiled South African freedom fighter Nimrod Sejake.

The Dublin of 1984 was a different place then, and Sejake was the first black person Manning and her colleagues had ever seen in real life. She said that his presence on the picket line was a turning point for her and her colleagues.

In her book, she describes Sejake as a quiet and unassuming man in his mid-60s. She recalls his response to a question about what his homeland was really like.

“He held up his right hand as though there were a glass in it and said: ‘You have to imagine South Africa as a pint of Guinness – the vast majority of it is black and a tiny minority is white – and just like a freshly poured pint, the white sits firmly on top of the black.'”

Manning said this depiction painted a vivid picture of the reality in South Africa in her mind than at any point since the strike started.

As the months progressed, she and her colleagues got a few knocks, even as support for them and their profile grew.

Manning said Dunnes management refused outright to negotiate or meet with them. In addition, she said, the head of the Irish Anti- Apartheid Movement, Kader Asmal withdrew his support for the strike.

She said they all were harassed regularly by the gardaí (police) on the picket line at this time.

“We got an awful lot of knocks back. People who we thought would have supported us: the Church, the government – who were all members of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement at the time,” Manning said.

“And one by one they either tried to distance themselves from us, or the government just didn’t support us at all. We didn’t want the law to change but that’s what happened in the end – what we wanted was the right not to have to handle South African goods.”

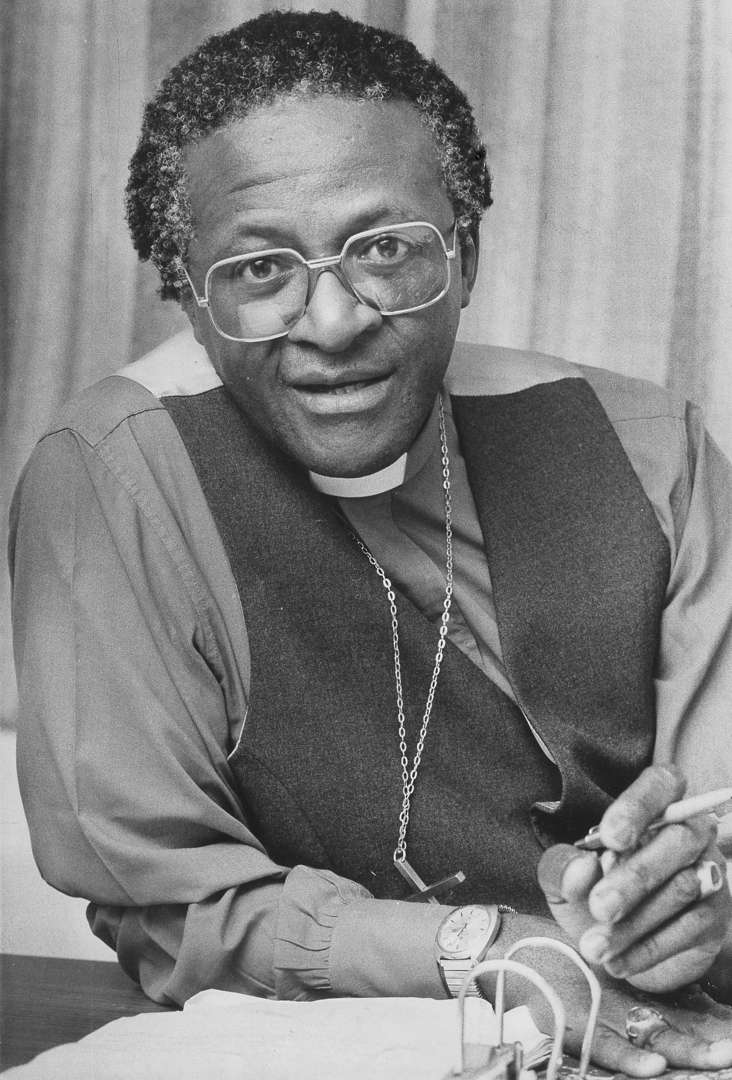

The Dunnes strikers were given their greatest endorsement when the South African Bishop Desmond Tutu – at the time a vocal and renowned critic of apartheid – asked to meet them as he travelled to collect his Nobel Peace Prize in the December after the strike started.

It’s then then attitudes in Ireland changed. Manning and Karen Gearon travelled to London Heathrow where they were interviewed by the international press, and their profile grew considerably.

They travelled to South Africa at the invitation of Tutu, only to be detained under armed guard for 12 hours at the then named Jan Smuts International Airport (now OR Tambo International) before being sent back to Ireland.

The anti-Apartheid strikers also travelled to other countries for speaking engagements, marched through Dublin with thousands of supporters and they drew praise and criticism from various high-profile names and personalities.

In the end though, they prevailed.

Their actions forced the Irish government to pass laws banning the importation and sale of South African goods, a ban that remained in place until the end of the apartheid regime.

When asked about the strike, how it changed her life and if she would do it again, Manning had no doubts. “I’m very proud of what we did. It was something that we achieved. We feel like we achieved it.”

“Whether the government ever admit it or not. There are probably things we would have done differently but we never would have changed it. Still to this day I always say I’d do it again.”

When Nelson Mandela met with them in Dublin in 1990, Manning said he told them that the courageous stand the twelve Dunnes Store workers took helped him to keep going during his time in prison.

A number of the them attended the former South African leader’s funeral.