The passage of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2019 in both houses of the Indian parliament seeks to give Indian nationality to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians who migrated to India from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan who are facing alleged religious persecution.

The exclusion of Muslims from the bill has resulted in widespread protests in India and condemnation from other parts of the world.

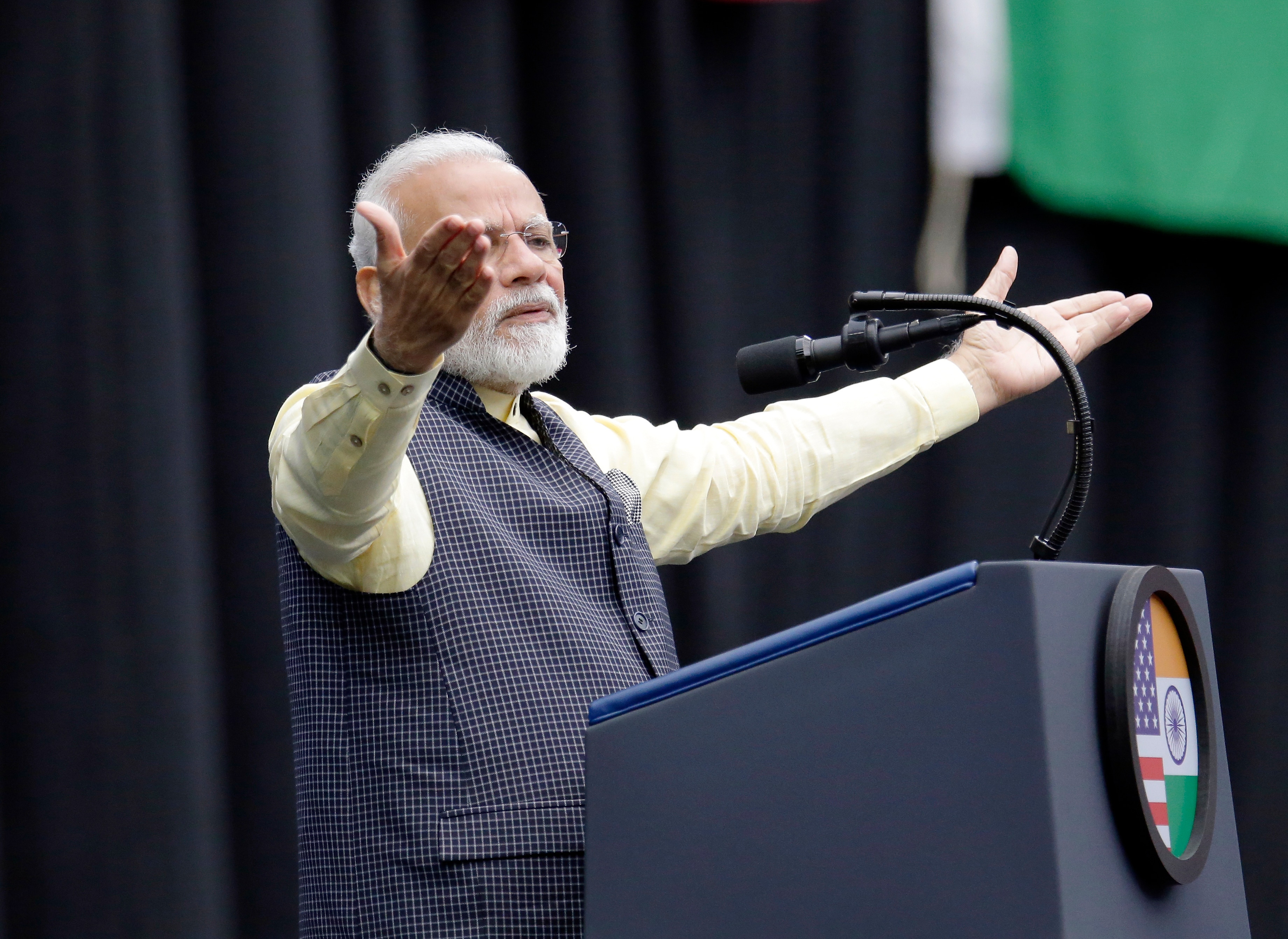

The Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, argues that Muslims were not included in the bill because they could not have faced religious persecution in those Muslim-majority countries and thus would have come to India of their own volition as economic migrants.

This is specious logic as the bill does not cover around 60,000 Tamil Hindus, Christians and Muslims who fled Sri Lanka during the civil war.

There has also been a large influx of Rohingya Muslims into India due to religious persecution by Buddhists in neighbouring Myanmar.

The bill is an infringement of the Indian constitution, which, under Article 14, guarantees not just “equality before the law” but also “equal protection of the laws” of the country.

Further, Article 15 prohibits the state from discriminating against any citizen on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.

Opposition to the bill has been particularly loud in the multi-ethnic state of Assam, where anti-immigrant sentiment has been strong for more than half a century.

The locals fear that illegal immigrants will become a burden not only on their resources and take way jobs but are also likely to pose a threat to the local culture, traditions and language.

In 1979, before a by-election for a parliamentary seat in Assam, observers noticed a massive increase in the number of voters, which student and political groups attributed to illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

This sparked riots and protests, in which over 800 people died over six years, until the Indian government signed the “Assam Accord” in 1985.

Under the accord, ‘foreigners’ who entered and illegally remained in the country before March 25, 1971, the day before Bangladesh declared independence from Pakistan, would be deported.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, however, sets a new cut-off date of December 31, 2014, allowing all undocumented Hindu immigrants who sought refuge in Assam on grounds of religious persecution before that date to stay on.

The bill is thus being seen in Assam as the central government reneging on the Assam Accord.

It appears that the bill was rushed through without analysing the possible repercussions, with the intention of accommodating non-Muslims who had been declared illegal immigrants by the National Register of Citizens for Assam, published on August 31.

It is estimated that nearly 2 million people, who had entered India after the cut-off date of the Assam Accord, were rightly excluded from the list of citizens.

The National Register, unlike the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, did not make religion a consideration when determining a person’s legal status.

The real challenge before the government is how to deal with those declared illegal immigrants living in India, especially the many from Bangladesh.

While Bangladesh’s foreign minister has asked India for a list of illegal immigrants from his country and says Bangladesh will allow them to return, their future remains as bleak and uncertain as that of the Rohingya Muslims.

Bangladesh. meanwhile, has taken strong exception to the use of the words “religious persecution” in the bill. In protest, Bangladesh cancelled the visits of two of its ministers to India.

The Modi government should enact an ordinance to include Muslims to avoid the bill being struck down by the Supreme Court on grounds of it violating the Indian Constitution.

India is already facing an international outcry after it abrogated Article 370, which gave special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill will further damage the country’s reputation internationally.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has criticised the bill for being “fundamentally discriminatory” while the US’s federal Commission for International Religious Freedom has called for sanctions against India’s home minister and other top leaders for “creating a religious test for Indian citizenship that would strip citizenship from millions of Muslims.”

At a time when the government has planned a year-long series of activities to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the country is moving away from its rich tradition of cultural pluralism and syncretism.

For centuries, India has given sanctuary to all people persecuted on grounds of religion, from Jews and Christians to Parsis and Bohra Muslims. Sadly, we now seem to be veering away from Gandhi’s secular India to an Orwellian state.

K.S. Venkatachalam is a management consultant. He writes on socioeconomic and human rights issues.

This article first appeared in the South China Morning Post.