By Lindsey Bahr

No one knew what Quentin Tarantino had in the duffle bag.

He and many other A-listers were gathered recently at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles for its glitzy annual fundraising gala. Tarantino was among the honorees. And as he approached the podium to make his speech, the bag did not go unnoticed. At the very least, it was unusual.

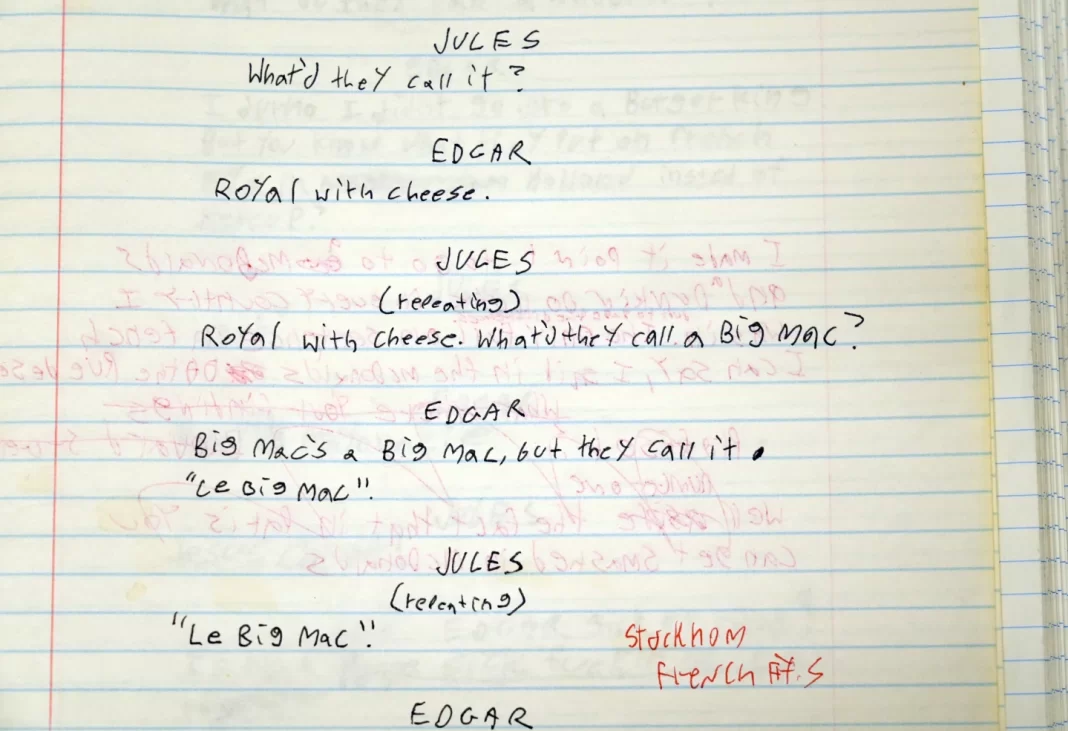

Then he opened it up and presented its contents: It was his original handwritten script for “Pulp Fiction,” with mistakes, misspellings and all. He was giving it to the museum.

“The script is legendary,” said Matt Severson, the executive vice president of academy collection and preservation. “No one was expecting it. This was not a coordinated effort on the part of the academy. This is Quentin thinking what can he do to make his stamp on the museum?”

It’s one of many high-profile acquisitions to the Academy Museum’s vast film memorabilia collection that the organization announced Thursday, including original “Ponyo” art by Hayao Miyazaki, glasses worn by Mink Stole in “Pink Flamingos,” Kurt Russell’s Snake Plissken costume from “John Carpenter’s Escape from L.A.,” animator maquettes of Figaro and Geppetto from Disney’s “Pinocchio” and six storyboards from “The Silence of the Lambs.”

The museum has also acquired personal collections of filmmakers Paul Verhoeven, Barbara Kopple, Nicole Holofcener, Oliver Stone and Curtis Hanson, as well as 70mm prints of Christopher Nolan’s best-picture winner “Oppenheimer,” and David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Ryan’s Daughter.”

“We want items from the history of cinema that relate to all ages and levels of interest,” Severson said. “We are preserving this global film history. And it’s something that the academy has been doing since its founding in 1927.”

Some are coming directly from the stars themselves: Jamie Lee Curtis gifted her tearaway dress from “True Lies,” Bette Midler gave two of her ensembles from “The Rose” and Lou Diamond Phillips contributed the guitar he used as Ritchie Valens in “La Bamba.” Others are through estates and private collectors. Just last year Steven Spielberg donated his collection of original, hand-drawn nitrate animation cells from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Studio Ghibli, which doesn’t work with any other American museum, donated more than 80 pieces of original animation art by Miyazaki and Noboru Yoshida, as well as the studio’s Japanese movie posters and an animators desk used at the studio.

“To have original artwork from Miyazaki? It takes your breath away,” Severson said.

The Academy Museum has more than 52 million items in its collection — the largest in the world — spanning the history of cinema. Not everything is on display, but components of the Academy’s collection can be accessed several ways: The museum itself, the Margaret Herrick Library, the Academy Film Archive and online.

At the gala, Severson heard from the likes of Nicole Kidman, Demi Moore, Jeff Goldblum and Tarantino how passionate they are about the work the museum is doing. He was quick to point out that it all starts with the staff working to preserve and present all the items in the best way possible. That includes the film preservation team and the paper conservators who aren’t just binding books but restoring photographs and posters damaged over time, as well as the team who spent an enormous amount of time bringing the belt from the 1982 film “Tron,” which had partially dissolved, back to life.

“You may not be aware of the painstaking labor that goes into preserving those objects,” Severson said. “It is important to pass this knowledge on to new generations of creatives and young filmmakers and artists to understand the history of the art form.

“This museum does become a platform that showcases our dynamic history and not just the history of Hollywood, but the global film industry.”

AP