By Sibi Arasu, Melina Walling and Seth Borenstein

United Nations climate talks resumed Monday with negotiators urged to make progress on a stalled-out deal that could see developing countries get more money to spend on clean energy and adapting to climate-charged weather extremes.

U.N. Climate Change executive secretary Simon Stiell called for countries to “cut the theatrics and get down to real business.”

“We will only get the job done if Parties are prepared to step forward in parallel, bringing us closer to common ground,” Stiell said to a room of delegates in Baku, Azerbaijan. “I know we can get this done.”

Climate and environment ministers from around the world have arrived at the summit to help push the talks forward.

“Politicians have the power to reach a fair and ambitious deal,” said COP29 President Mukhtar Babayev at a press conference at the venue. “They must deliver and engage immediately and constructively.”

Climate cash is still a sticking point

Talks in Baku are focused on getting more climate cash for developing countries to transition away from fossil fuels, adapt to climate change and pay for damages caused by extreme weather. But countries are far apart on how much money that will require.

A group of developing nations last week put the sum at $1.3 trillion, while rich countries are yet to name a figure. Several experts estimated that the money needed for climate finance is around $1 trillion.

“We all know it is never easy in politics and in international politics to talk about money, but the cost of action today is, as a matter of fact, much lower than the cost of inaction,” said Wopke Hoekstra, the EU climate commissioner at press conference.

“We will continue to lead to do our fair share and even more than our fair share, as we’ve always done,” he said. But Hoekstra added that “others have a responsibility to contribute based on their emissions and based on their economic growth too.”

Teresa Anderson, the Global Lead on Climate Justice at ActionAid International, was skeptical about rich countries’ intentions.

“The concern is that the pressure to add developing countries to the list of contributors is not, in fact, about raising more money for frontline countries,” Anderson said. “Rich countries are just trying to point the finger and have an excuse to provide less finance. That’s not the way to address runaway climate breakdown, and is a distraction from the real issues at stake.”

Rachel Cleetus from the Union of Concerned Scientists said $1 trillion in global climate funds “is going to look like a bargain five, 10 years from now.”

“We’re going to wonder why we didn’t take that and run with it,” she said, citing a multitude of costly recent extreme weather events from flooding in Spain to hurricanes Helene and Milton in the United States.

Robert Habeck, Germany’s climate and economic affairs minister said rich nations shouldn’t try to stop developing nations from producing more energy, but it has to come from cleaner sources.

“They have the same right to create (the) same work, same education and health system,” he said. “On other hand, if … they are doing the same as we did for 100 years of burning fossil energy, that is completely messed up.”

Alongside U.K. energy minister Ed Miliband, Habeck announced around $1.3 billion on Monday for developing countries to move away from fossil fuels.

“The industrialized countries are committed to their climate financing, while at the same time we are bringing more private investors and donors on board and broadening the donor base,” Habeck said.

Climate watchers keep an eye on Rio and Paris

Meanwhile, the world’s biggest decision makers are halfway around the world as another major summit convenes. Brazil is hosting the Group of 20 summit Monday and Tuesday that brings together many of the world’s largest economies. Climate change — among other major topics like rising global tensions and poverty — will be on the agenda.

COP President Babayev said the world “cannot succeed” in its climate goals without G20 nations.

“We urge them to use the G20 meeting to send a positive signal of their commitment to addressing the climate crisis. We want them to provide clear mandates to deliver,” he said.

Harjeet Singh, global engagement director for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, said G20 nations “cannot turn their backs on the reality of their historical emissions and the responsibility that comes with it.”

“They must commit to trillions in public finance,” he said.

Also on Monday, the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has been mulling a proposal to cut public spending for foreign fossil fuel projects. The OECD — made up of 38 member countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan and Germany — are discussing a deal that could prevent up to $40 billion worth of carbon-polluting projects.

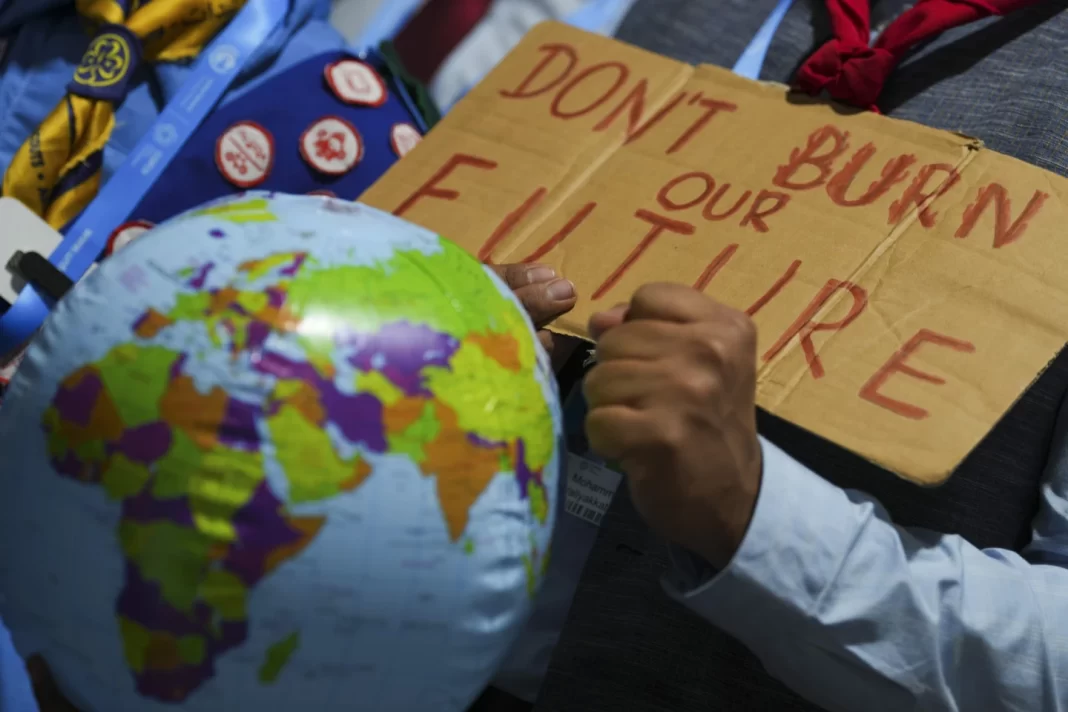

At COP29, activists are protesting the U.S., South Korea, Japan, and Turkey who they say are the key holdouts preventing that OECD agreement from being finalized.

“It’s of critical importance that President Biden comes out in support. We know it’s really important that he lands a deal that Trump cannot undo. This can be really important for Biden’s legacy,” said Lauri van der Burg, Global Public Finance Lead at Oil Change international. “If he comes around, this will help mount pressure on other laggards including Korea, Turkey and Japan.”

AP