By Eghosa E. Osaghae

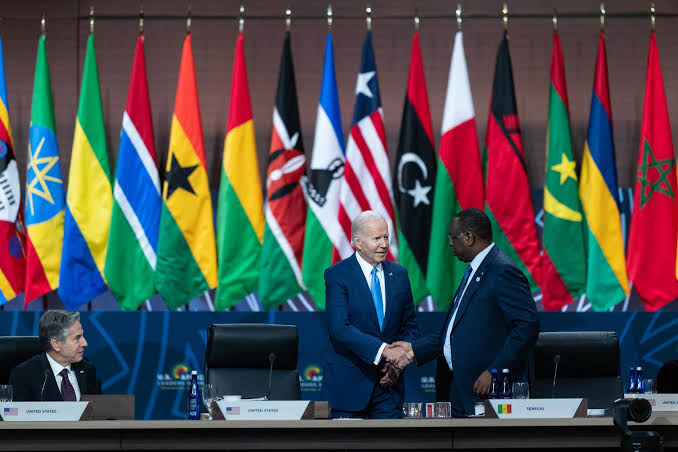

U.S. presidential elections have always been of interest to Africa because of the crucial role the United States plays in the stability and development of the continent. Interest in the forthcoming election is particularly high because of the widespread perception across Africa that its strategic relevance to the United States has waned in the recent past―leading to relegation, neglect, and a lack of empathy.

This comes against the backdrop of the debilitating situation in many parts of the continent, marked by deteriorating state fragility, increased poverty, poor public health, conflicts, terrorism, insecurity, democratic reversals, huge foreign debts, and the ravages of climate change. Those pressing issues require greater support from the United States, arguably Africa’s greatest ally.

To date, the United States’ involvement on the continent has focused primarily on humanitarian and democratic interventions. While these are helpful, they have been at the expense of more critical engagements around development goals such as reducing debt problems, mitigating state fragility, and addressing the harms of climate change. This has given room to rival superpowers such as Russia and China whose inroads have expanded rapidly.

Thus, the hope in Africa is that the U.S. presidential election can provide the opportunity for a positive reengagement with the continent’s flashpoints of decay and instability. Part of that hope is that the United States will support the reform and strengthening of the UN and other multilateral bodies to make them more inclusive and equitable agents of global governance. Developments in Sudan, Congo, and the countries of the Sahel―all of which have seen geopolitical realignment toward China and Russia―have already signaled growing discontent and impatience with the West as Africa struggles to surmount its existential challenges.

It remains to be seen if the forthcoming U.S. presidential election will make the United States more responsive to Africa. If the debates and policy discussions in which Africa has featured very tangentially are anything to go by, the chances of a fundamental shift appear quite slim. Still, the hope is that a more liberal globalist policy posture will offer room for renegotiating a new trajectory of U.S.-Africa relations that addresses Africa qua Africa.

This realignment of U.S.-Africa relations will certainly require a tempering of the U.S.-centric rhetoric that has driven conversations on immigration, trade, aid, and multilateralism. However, this realignment is necessary if the United States is going to successfully compete with China and Russia on the continent.

Osaghae is Director-General, Nigerian Institute of International Affairs.

This article was originally published in the Council of Councils.